“But I have leapt down into the flux of time where all is confusion to me.

-Augustine of Hippo

The Lord is not slow to fulfill his promise as some count slowness, but is patient toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance.

-2 Peter 3.9

If you know anything about Norm Macdonald is that his career has been one of risk and the pursuit of the perfect joke. He is my all time favorite comedian. I could listen to the same jokes and clips of him found on youtube over and over and still laugh every time. In a radio interview, amidst the shallow and vapid dialogue, Macdonald said something quite startling and revealing:

“I came to the conclusion that we’re all plunging headlong into death… I try to look at life square in the eye. As terrifying as it is, it is the most terrifying thing there is. Being alive means dying.“

This statement inspired three strands of reflection about time and death. Both have to do first with the human experience of the cursedness of time and of death; Second, how both are experienced disconnected from an eschatology; and third how God is redeeming time and how death needs to be seen in the light of Christ’s redeeming work. Somehow it will all relate to the comedy of Norm Macdonald, who loves to linger within a long drawn out joke. This to me signals something of the eternal peaking through in Macdonald’s comedy.

The Horror of Time

And the world is passing away along with its desires, but whoever does the will of God abides forever.

-1 John 2.17

Dietrich Bonhoeffer gave a sermon on the verse cited just above. In it he reflects on the horror of time:

“The great philosopher of the ancient Greeks, Heraclitus of Ephesus summarized his most profound insight regarding the world within words: all things are in flux…Nothing abides, nothing is secure, nothing is assured in the world…meaning that just when you want to seize life, it already has passed by, slipping through your hands, melting away like nothing. Life does not live; it dies. To live means to die.”

This is the horror of time: time treads on the journey towards death mercilessly. Being alive means dying. We have no ability to change time, nor do we have the ability to change what has been done in time. Bonhoeffer notes, “whatever happens remains something that has happened; it can never be undone…Guilt remains guilt, omission remains omission…what has happened, has happened for all time.” To cite Ecclesiastes:

“What has been is what will be,

and what has been done is what will be done,

and there is nothing new under the sun.” (1.9)

As we experience this marching on of time, we experience it as merciless. It gives no care to our feelings, to-do lists, nor anything else that we deem important in our lives. Even in our accomplishments and successes, there is a lingering emptiness and we become aware that we are still not whole.

In the British television show Broadchurch, DI Alec Hardy (played by David Tennant) is seeking to solve an unsolved case from two years prior. It haunted him, as he was the lead detective on the case. At the end of the second season he finally solves the case, after nearly committing suicide because the horror of what had taken place, there is a moment after hearing the truth of what happened he finds himself alone in a room weeping over the tragedy. Following this Hardy has a sense of just how many lives have been destroyed, and how this destruction is still real and concrete even after some sense of true justice has been carried out. Hardy feels the horror of time and how, in the words of Bonhoeffer, “what happens remains something that has happened; it can never be undone…” Death it seems, has the final word over our lives. For us moderns death is only seen as a cursed interruption. We do not know what to do with it except for put it out of our minds as long as we can, all the while it is all around us and its sting will be felt by all.

Death as an Interruption

Without immortality, every human existence contemplated as such must end in despair; for death is, visibly speaking, the last word.

-Dietrich von Hildebrand

Going back to Macdonald’s statement about how “being alive means dying”, this is an insightful one into the modern perception of death; the dreadful end of a directionless existence. Sure we have existence, but this existence is accidental and the cosmos does not care whether we are here or not. Life is cold and distant, To combat this dread many individuals work to prolong this as much as they can. Health, writes philosopher Byung-Chul Han, today is an absolute value. Han notes:

“His long, healthy, yet uneventful life finally becomes unbearable to him, and so he turns to drugs, and in the end is killed by drugs: ‘A little poison now and then: that produces pleasant dreams. And a lot of poison at last, for a pleasant death.’ He seeks to extend his life to infinity through a rigorous politics of health, yet it is paradoxically cut short even before his time has come. Instead of dying, he comes to an end in non-time.“

Han in his book “The Scent of Time” makes the argument that time is no longer something that has duration. We seek to throw off the “chains” of tradition and structures in the name of freedom, and by doing so lose a grip on duration:

“Life is no longer embedded in any ordering structures or coordinates that would found duration. Even things with which we identify are fleeting and ephemeral. Thus, we become radically transient ourselves… When time loses all rhythm, when it dissipates into the open without any hold or direction, then all right or good time also disappears… The right time, or the right moment, only arises out of the temporal tension within a time that has a direction.”

We are transient because our notion of time is transient. We feel out of control and therefore we attempt to take control of our lives by having control over our time in the day. Theologian John Swinton helpfully writes that:

“Time is assumed to be something that can be broken down into small, practical components that can then be used as currency within various “marketplaces,” be they economic, political, relational, psychological, or spiritual. Time is perceived as fragmented, commodifiable, scheduled, and, above all, instrumental.”

Our very notion of what time is does not allow for it to have duration, one over arching narrative that has meaningful connections. It is fundamentally fragmented, and in some way leaves us fragmented in ourselves. We want to keep parts of our lives separate, and by this we can keep some things in one box and some things in another. There is no space for duration, wholeness, and worst of all, lingering. If we linger too long, we have wasted time. If time is not used within the framework we have constructed, it is misused time and we are guilty of misusing it. In the event of death, which will come to us all, we will all be found guilty under the law of the western clock. Wasted time, mismanaged lives filled with regret and despair. What are we to do? Does death have the final word over who we are in the end?

Redeemed Time

“The last enemy to be destroyed is death.”

-1 Corinthians 15.26

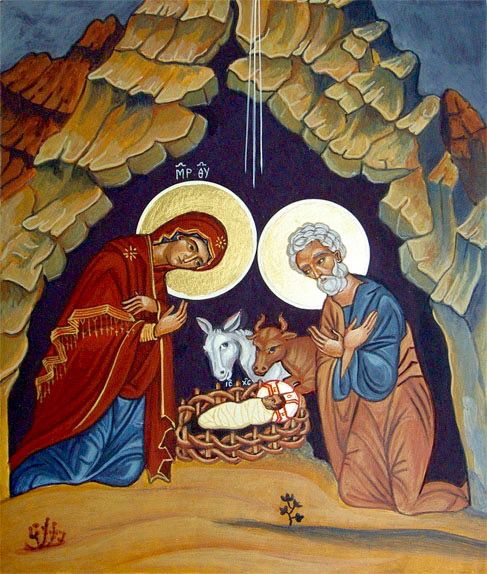

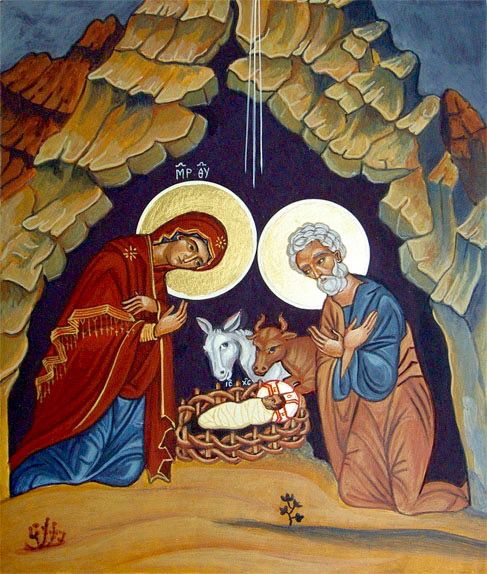

The heart of redeemed time is fundamentally begun at the Incarnation of the Lord Jesus. Joseph Ratzinger reflects on the significance of the Incarnation:

“All time is God’s time. When the eternal Word assumed human existence at his Incarnation, he also assumed temporality. He drew time into the sphere of eternity. Christ is himself the bridge between time and eternity…now the Eternal One himself has taken time to himself…In the Word incarnate, who remains man forever, the presence of eternity with time becomes bodily and concrete.”

The very act of God entering into temporality means that time is not out of control, or transient, but time has a very specific end point. This is bound up in the person and work of Christ. Time is Christ shaped, as John Swinton puts it. He writes:

“Scripture is quite clear that God’s time contains the shape and form of Jesus: the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end (Rev 22:13). The ethos and movement of time and history is Christ shaped. Jesus is time in the sense that in Christ human beings can see clearly what time looks like and what time is for. If this is so, then God’s time not only contains gentleness, it is gentleness. Gentleness is written into the heart of the universe. God’s time is gentle time.”

Here I want to mention the importance of the worship of the Church as practicing the very heart of what God’s time is. In terms of liturgy and the liturgical church calendar, the Church enters into the true time: the eternal time breaking forth into the temporal order. This practice of daily Sunday church attendance, while seemingly mundane and ordinary, actually begins to shape our lives in a way that draws us into the reality of the triune God which is fundamentally love. Love is the core of reality itself. As Swinton notes above, Christ helps us to see what time is for and what character it takes. It is one of gentleness and slowness. It is a rejection of the modern clock, and in the act of worship we come to know that our time is a gift and we must orient that gift and give it back to God. This orientation comes about by deceptively mundane practices; weekly worship, eucharist, prayer, forgiving others etc. Through these time begins to take a more gentle shape, and slower pace. Most fundamentally, however, our union with Christ also gives a new perspective and shape to death.

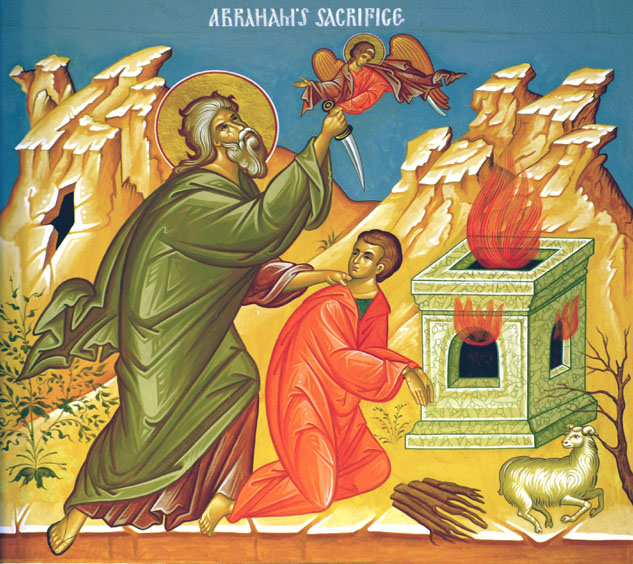

Time and death are also connected by Christ, in his incarnation, death and resurrection. Time is given a proper shape and orientation. Paul writes “But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons.” (Gal 4.4-5) In this coming, by our baptism we are united to him in his death. “We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life…Now if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him…So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus.” (Rom 6.4, 8 & 11) In our union with Him, death does not have the final word over our lives, nor over the whole created order. Athanasius puts it perfectly:

“By man death has gained its power over men; by the Word made Man death has been destroyed and life raised up anew. That is what Paul says, that true servant of Christ: “For since by man came death, by man came also the resurrection of the dead. Just as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15:21-22).”

Christ, to cite St. Paul again, “…gave himself as a ransom for all, which is the testimony given at the proper time.” (1 Tim 2.6) Death and time are no longer cursed, and the truth for human beings is that in the coming of Christ is the end of all cursedness and despair. For God has stooped low and taken all of it on himself to rescue us from the domain of darkness.

Lingering (Redemption)

Back to Norm. What I love most about his comedy is that there is a slowness to it. Whether its a six minute joke about a boy named Dirty Johnny, or a four minute moth joke, the joy of lingering is to be found. This creates a duration, a connective tissue in the fabric of time. This is where the eternal peaks through the comedy of Norm Macdonald. The long drawn out sentences and seemingly pointless dialogue ultimately serves the purpose of the punch line; aka the eschaton. The small details are not meaningless, but are given meaning by the punch line. This is utterly opposed by historical time, because if the small details do not serve some purpose to progress, they are a waste of time. Byung-Chul Han observes:

“Historical time can rush ahead because it does not rest in itself, because its centre of gravity is not in the present. It does (not) permit any genuine lingering. Any lingering only delays the progressive process….Time is meaningful insofar as it moves towards a goal.”

Redeemed time, as opposed to historical time, permits lingering. It permits joy, laughter, pleasure, beauty, slowness and rest because these are the true ways of being. God longs to linger with his creatures. Time is not only meaningful if we are rushing towards a goal, but the goal has already been accomplished by the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. To quote Han one final time:

“Time begins to emit a scent when it gains duration; when it is given a narrative or deep tension; when it gains depth and breadth, even space.”

Here the scent of redeemed time is that of Christ. St. Paul observes:

“For we are the aroma of Christ to God among those who are being saved and among those who are perishing, to one a fragrance from death to death, to the other a fragrance from life to life.”

The Christian should smell of slowness and gentleness. The aroma of Christ reshapes time, and thus our lives take on a the scent of redemption, and with it we may declare with Paul boldly:

“O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?”

References:

Han, Byung-Chul. The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering

Swinton, John. Becoming Friends of Time : Disability, Timefullness, and Gentle Discipleship.

Ratzinger, Jospeh. The Spirit of the Liturgy.